The Science of Gender and Sex

vwuf21isg89evwatmige

The Flags of Sexual IdentityImage via Filthy by Ossiana Tepfenhart

Happy Pride Month.

Having an entire month dedicated to something that many understand, but just as many do not can be quite jarring. But the true crime is in the use of outdated or cherry-picked scientific facts to support oppressive opinions.

While most have learned in our various schools that there are only two sex chromosomes, modern science has explained the various circumstances that can occur with them. Unfortunately, certain outlets for science news have their own agendas. If gender and sex are written about at all, they receive an article written in a nondescript narrative style, which is nowhere near enough to cover the science, given the topic. For example, Bill Nye, perhaps one of the most well-known modern science communicators, had an episode of his series, Bill Nye Saves The World, in which he discussed both gender and sexuality. Although convincing, they are not thorough.

In other words, although communicators remain on top of the news that comes out, there is a lack of complete coverage.

Let’s rectify that by, first, handling one of the biggest misconceptions in society regarding science.

Social Science Is Not Science

If you’ve heard this or said this, pay attention to why this is a fallacy.

The main definition of science, according to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary is simply “the state of knowing”. The word comes from a Latin word, scientia, which means “knowledge”. This knowledge can be gained through experimentation or observation, as we have seen throughout history. Suspending hyperbole, everything that we have built our societies on has come from general laws that we have discovered through observation or experimentation. We must know things in order to flourish and innovate. Therefore, knowledge is implicitly rooted in our humanity. Fetuses begin learning in the womb, toddlers look to their parents to learn what is acceptable in society, teenagers separate from their parents to practice what they’ve learned from them and to develop their own knowledge, and adults, ideally, will use the knowledge that they gain to improve society for their children.

I could be sophomoric and say, “Why would social science be called ‘social science’ if it’s not related to science?” But that’s not pragmatic. If we are aware that science is the pursuit of knowledge through observation or experimentation, then you must ask what the study of human society, including behaviors and relationships, is. After all, if we are not aware of why society functions the way it does, then we cannot hope to change the poor aspects of it.

This is, through and through, the definition of social science. And our psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, linguists, archaeologists, human geographers and political scientists should not be discounted. In fact, it is a paradox to believe in science and not acknowledge the research of these scientists.

Image via Pediaa

Building the Genetic Library

Before I even get to this, we need to acknowledge one fact that I alluded to already. Science grows with knowledge. There are things that you have been taught that are already outdated. With that said, maintain an open mind: if there are questions due to a lack of understanding, ask.

We are aware of two sex chromosomes, or allosomes, the ‘X’ and the ‘Y’ chromosomes, which we say “carries the genetic material for the determination of sex”. But I believe it an injustice to simply describe chromosomes as just “genetic material”. They do much to ensure that you are who you are.

In humans, a chromosome is a linear strand of one condensed DNA molecule. Within that one DNA molecule, there is a portion of the genome, or the complete library of genetic information. Therefore, there must be many DNA molecules in the body to accommodate the entirety of your genetic information. It has been established that there are 23 pairs or 46 chromosomes in one cell. We receive one set of 23 homologous chromosomes, or chromosomes of the same type, from each of our parents, making 46. This is done as a safeguard against diseases shared among two genetically similar people, but, more importantly, to ensure that there is a healthy copy of each gene.

22 of those pairs, or the autosomes, contain most of the information required for your body’s development. But the last pair, the aforementioned allosomes, contain the vast majority of sexual information. One allosome comes from your father and one comes from your mother explaining why the typical result of their combination is either XX or XY.

Allosomes are created through the process of meiosis (my-osis), which occurs in the ovaries or testes. The goal of this type of division is to create haploid cells, or cells with only 23 chromosomes, by splitting our diploid cells, or cells with 46 chromosomes, twice.

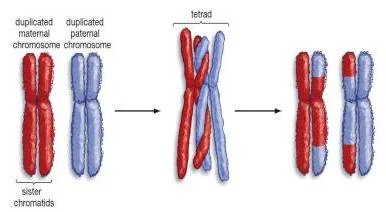

The first splitting, referred to as meiosis I, is very similar to ordinary cell division (mitosis). The cell that prepares for division creates an additional copy of each chromosome within the nucleus, or the cell’s processor. Each copy is called a chromatid, of which at this point, there are 92 - two for each of the 46 chromosomes; it is incredibly important to note that there are still 46 chromosomes. Those chromatids group together at their centromere, center, creating the traditional “X” shape that you may be familiar with right before division (they are not actually X-shaped at any time before this).

Image via MarshScience7

Unlike in mitosis, in meiosis, after the copies of each chromosome are made, each of those homologous chromosomes undergo synapsis, grouping together at their centromeres and creating groups of 4 chromatids. These are called tetrads, which literally means a group of four, or bivalents, which literally means two strong (probably referring to the two chromosomes and their strong connection - I don’t know, this name is kind of obtuse).

Image via Biology Exams 4 U

At the chiasma, the place where homologous recombination occurs, DNA sequences are exchanged between two identical molecules of DNA. This is why it is important that the chromosomes that grouped together are homologous, or of the same type. You wouldn’t want a recombination event of eye color into hair color, even if that was easily possible. After this recombination event, you have four completely different chromatids, and the tetrads separate.

Image via Amazing World of Science

At this point, the sister chromatids are still connected, meaning there are still 46 chromosomes. It would be a problem if a sperm cell with 46 chromosomes met an egg with 46 chromosomes because you would get a child with 92 chromosomes. And no human on earth exists with that many. Therefore, another round of splitting has to happen to separate the individual chromatids, creating haploid gametes - sex cells, such as the sperm and egg cells, that contain 23 chromosomes (not 23 pairs of chromosomes). We call this splitting meiosis II.

The following image summarize the entirety of meiosis, which we have just explained above:

Image via yourgenome

Rise of the Mutants

Now, I wonder if you see why we went through this yet. Look at the picture above again. How many steps does it take to get from a diploid cell to the haploid gametes?

That question’s answer is important. After all, mutations increase in probability with the increase in the number of steps of gene manipulation, like that in mitosis and meiosis. Genetic mutations are defined as alterations that take place within the gene, whether random or purposeful. So, if in meiosis, one of the sex cells is missing a chromosome, it contains a mutation. We call cells with this specific mutation aneuploid (an-yoo-ploid) cells.

Recalling again that meiosis produces both gametes, it follows that both sperm cells and egg cells can contain mutations. Now, imagine how many, of the trillions of cells that are made, are mutated. All of a sudden, mutations don’t sound too rare, do they?

The question that we need to ask is, “What happens when a mutation occurs?” Normally, any cell would undergo a process called apoptosis, or controlled cell death, upon its realization that something is not quite right. At any point, if the mutations are detected by the cell’s own checkpoints, the cell will most-likely die. However, some mutations slip through those checkpoints. More to the point, when mutated sex cells meet, become an embryo, and checkpoints detect the mutation, a miscarriage will result (not the only reason for miscarriages, just one of them). On the other hand, if the mutation gets past the checkpoints, and an embryo fully gestates and is born, then it is certain that the child will contain “abnormalities” (Current Biology, Volume 20, Issue 23). This is true of any chromosomal mutation. But our commenters above have a particular interest in the X and Y chromosomes, and so, we should look at this discussion in that scope.

But I’ll tell you what: we’ll go a step further. Let’s use their same argument to show them why they’re wrong.

The XY-Hangup

We are and have been aware for a long time that it is the sperm that determines maleness or femaleness; the sperm contains both the X and Y chromosome, while the egg only contains X chromosomes. Classically, the combination of two X chromosomes from the mother and father is said to result in a human female, whereas the the combination of an X and Y chromosome results in a human male.

You perceive this as “normal” because it is common social behavior to consider the majority as the normal. More specifically, because there are more humans that are XY or XX, you are more likely to consider this as the way things should be. How’s that for social science impacting your lives? The problem for some is that natural science doesn’t care for what we find socially convenient.

It is completely possible for a human to be born of an aneuploid cell and not have any critical defects that stunt their growth. A mutation that occurs in an allosome may have an effect on the body, but the effects may not be pronounced. These allosomic mutations can cause a few syndromes, or combination of symptoms, but the most noteable are Klinefelter’s, Triple/Trisomy X, Turner, and Partial/Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndromes. All of these have a common similarity: the effect of X and/or Y chromosomes vary regarding the development of the particular human.

So…let’s revisit the arguments.

“Everybody knows that there are only XX and XY combinations.”

No. There are not. We have covered that mutations can occur, in which expression of these sex chromosomes can vary. For example, one could have an extra X chromosome from their mother that doesn’t get inactivated by the body during growth. There are people that are born with one X and no Ys, like in Turner’s Syndrome, or three or four Xs, like in Trisomy and Tetrasomy X. There are people that have the karyotype, or chromosomal makeup, of XXY, XYY or even XXXXX.

“To believe that you identify as another gender is delusional.”

That’s as false as the above argument. For example, androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) is primarily experienced by someone with an XY combination. We would call that a man, but if you know what androgen insensitivity syndrome is, then you would understand why those with AIS do not feel like men. AIS is a disorder in which androgens, like testosterone, are either partially or completely ineffective. That, naturally, results in more feminine features and development, despite being XY. Likewise, there is an estrogen insensitivity syndrome (EIS) that is, basically, the exact opposite. Exposure to estrogen and testosterone or their ability to be received can directly affect the mindset, whether conventionally feminine or masculine, of the organism. This is fact.

“Science claims that other genders and sexes do not exist.”

Science is a convention. Conventions are at the whims of those that develop them. Do not forget that science, as a system to grow knowledge, is implicitly growing as we research and observe further. Science may give us tools to learn, yet it is still only as powerful as the knowledge that we have. But due to science being innate in our humanity, it is ensured to grow as long as humanity seeks new knowledge. One using science as an argument must expect that their understanding will be incomplete or even incorrect at some point in time.

“Sex and gender are determined by biology. Whatever you want to say about them, this is true.”

See the first, second and third arguments above this one. Also, remember that it is society that has determined that XY is a man and XX is a woman. So if social science does not matter, then do you also say that society’s behavior doesn’t matter, or does social science actually matter and you admit that it has yet to study the issues of gender and sex enough, just like natural science.

“So their gender is a result of a mutation? Isn’t that a bad thing?”

Hoo boy. This is loaded. You are a mutant. This simple truth is why you look different than the last person you saw or, if you have a twin, you both look different than your parents. It’s also why we have similar genetics to yeast, while not being yeast. Mutation is only given a bad connotation because of the negative effects of it, yet there are plenty of good mutations. After all, they are why we have survived on earth for this long. Mutations have also not stopped us from caring for those with diseases, syndromes or disorders. Do not use this argument as an excuse to oppress someone…It’s, literally, inhuman.

Human Resilience

This has went on for too long, but there’s just one more thing to say to those struggling with gender identity and sexual orientation.

There is one very important factor that I mentioned, but glossed over. Yes, social environment may have a hand in your identity or orientation, yet so does your genetic makeup. While neither natural science or social science are adept enough to explain everything, we do know that, in many cases, genetic variability brought on by mutation could have easily ended your lives before it even began. The fact that you are still here, reading this, is a testament to your importance. Not only for our understanding, but for our advancement. I urge you to recognize that your uniqueness, your difference from that of the “normal”, is only a good thing. And that those that consider it a bad thing are either lacking an understanding and are unwilling to look for it, or are afraid that their way of life will be disturbed. Do not cower in the face of someone that does not understand.

And for those that do not understand, making excuses because they “haven’t seen anything about it”: it is not the responsibility of the science communicator to be accountable for your knowledge; it is our job to provide the content for you to digest. You must take it upon yourselves to be informed, even if it disagrees with your known beliefs.